BPM home | Volume 7 index | Article

Why must we provide a stage for the subject in musical analysis? For what reason must it be permissible for the subject to speak?

Fundamental to Julia Kristeva's psychoanalytic theory of abjection is her distinction between the "semiotic" and the "symbolic", the two elements out of which all signification is composed.2 The symbolic is associated with the grammar and structure of signification. It makes reference possible through the symbolic structure of language. On the other hand the semiotic represents the bodily drives associated with the rhythms, tones, and movement of signifying practices. Throughout her work Kristeva constantly reminds us of the body's presence, function, and essentiality. To state this may seem all too obvious. However, despite widespread awareness of Kristeva's discussions of the bodily, academics are still far from comfortable with its implications. Whilst it is acceptable to state that there could be no signification without the symbolic (since everything would become babble), it remains problematic to assert that signification would be equally meaningless without the semiotic. We must accept that without the bodily – the semiotic, signification would have no importance for our lives. Ultimately then signification requires the combination of both the symbolic and semiotic.

Why integrate the body into academia? Focussing on the dialectical relationship between the symbolic and the semiotic allows us to initiate a process of introspection through which we can scrutinize our own thoughts and our own writing in order to attempt to trace how the two strands inform one another. When confronted with a powerful emotional reaction to a piece of music such as Alban Berg's Altenberglieder (discussed in this paper below) we must ensure that we narrate that experience fairly and accurately. Using a theory such as Kristeva's would therefore seem both viable and natural. This is not to imply that the contingent nature of such a pairing renders it an entirely random, or optional choice. In fact contingency itself might be interpreted as a semiotic process since it is without preordination, stemming instead from an urge towards something to which we feel ourselves inclined. The strong emotional and personal nature of a listening such as this requires us to write about it in such a way as to foreground these aspects. Traditional tools of academic discourse encourage us to 'interpret' music in order to ascribe meaning to the sound. Yet in a case such as this we must construct a mode of expression with which to approach an investigation a posteriori. We must 'narrate'. Unlike interpretation, which is bound by a goal of extracting a value out of listening, narration can preserve the central position of the event itself. Narration is a disclosing of signification, it clears a space on which to stage the subject's true 'reading of a listening'.

This brief paper marks the very beginning of what I hope will become a much larger project exploring twelve-tone music using theories of psychoanalysis. Not only does this body of theory 'fit' the musical genre historically but from my work so far I also have reason to believe that experimenting with psychoanalytic theory can offer interpretative openings onto what might be referred to as the 'emotional work' performed by music as we listen.

The discussion herein concentrates on the position of tonality within twelve-tone composition. What happens when we listen to a piece of serial music: how do we attempt to make sense of it, to order it, to familiarise ourselves with it, to interpret and ultimately understand it? How do the aims of traditional musical analysis shape our listening and interpretation of a twelve-tone composition? I would like to examine the syntax of listening, to acknowledge the fact that I am always trying to catalogue as I listen, attempting to assign a function to any tonal inflection in order to find a position for the alien musical material within the boundaries of my known musical language. I believe that we must try to scrutinize the processes that take place when we choose to listen with the aim of analysing, what must we do to that music in order to obtain our desired results?

Tonality is one of the major musical aspects, along with others such as phrasing and form, which allows us to centre ourselves as listeners within a piece. The powerful effect of such familiarity within music is a subject that has been widely discussed, particularly in pop music studies, for example by Adorno in his essay 'On the Fetish-Character in Music and the Regression of Listening'.3 In this essay Adorno talks of the persuasive nature of sounds that, through merit of their familiarity alone, seduce the listener, making him or her associate them with something positive, with quality. There can be no doubt that in our western musical environment 'textbook tonality' and internalised harmonic progressions are prime exemplars of such familiarity: of the known and knowable within musical language. However I wish to suggest that when we set about interpreting a piece of twelve-tone music our reaction to the tonal familiar is quite different from that set out in Adorno's essay.

In his 1967 book Music, The Arts and Ideas,4 Leonard Meyer highlights that early learning conditions the listener to the perception of tonal but not twelve-tone music. It is the absence of such conditioning that denies the twelve-tone work what Lévi-Strauss calls a 'primary level of articulation'5 necessary to establish the listener's expectations. I am interested in how moments of familiar tonality that occur within the context of unfamiliar, disorienting twelve-tone music are received and assimilated by the listener in the absence of a 'primary level of articulation'.

I'm going to spend some time looking in a bit more depth at one of Alban Berg's Orchestral Songs, the Altenberglieder. There are various reasons for choosing this as a test piece for such an investigation. In the introduction to the Universal Edition short score, editor Mark DeVoto talks of these relatively early songs (mostly composed in 1912) as contributors to "the historic development that culminated in Schoenberg's twelve-tone technique"6. However, more significant to this paper is the fact that the songs also illustrate that serialism is not always exclusive from tonality even though it has most usually been employed as a means of erecting pitch structures in atonal music. The fifth Altenberg song is a passacaglia whose main theme comprises of a twelve-note row, yet as Berg himself says in a letter to Schoenberg dated 9 March 1913 "the harmony is still almost tonal"7.

Throughout the fifty-five bars of this short song Berg consistently appears to tease his listener with 'straight' tonal references, some of which are more subtlety integrated than others. Though, as DeVoto also points out, it is clear from the limited fabric of the song (three principal repeated motives and two subsidiary ones), that Berg's composition betrays a serialist inclination, these repeated themes are manipulated in such a way as to result in tonal references that often seem so leading and overt to the listener that the resulting sentiment of familiarity is far from reassuring or supportive of its twelve-tone opposite. When confronted with tonality in this setting I would argue that we experience something of an emotional reversal. I no longer desire the familiarity of the tonal reference point since I find in it no comfort. As soon as I come into contact with the tradition with which I am so familiar, it is transformed. The familiarity is now disruptive, threatening and repulsive.

It is this emotional reversal that first led me to Julia Kristeva's theory of abjection8. She explains that it is not simply the case that the listening subject's identification and subsequent interpretation of tonality is literally turned inside out, precisely reflected and transformed from something comforting to something repulsive. Instead, a paradox exists in which the listener desires the identification of the traditional, the known entity; yet as soon as we encounter it directly it becomes repellent. I will come back to this theory in more precise detail in a moment but first I will show exactly what I mean by reference to Berg's passacaglia itself.

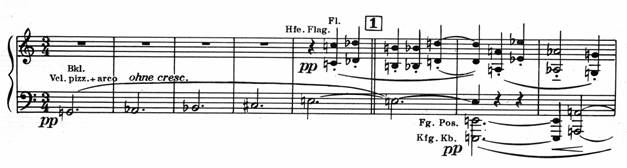

Example 1 © 1953 by Universal Edition (Vienna)

The first thing that we hear is the passacaglia theme stated in unison by cellos and bass clarinet. Both the unchanging pianissimo dynamic as well as Berg's specific marking "ohne crescendo" ensure that the melody sounds unapologetically flat or stale. Other than the timbre of this combination of instruments, the only thing that characterises the passage is the intervallic relationships between the notes of the row. So right from the very opening of the movement I am listening to tones asking: how can I understand the evolution of this succession using the tools of my traditional vocabulary? The total lack of event forces me to concentrate on assigning a possible tonality to the material.

When I am listening to this passage my ear inadvertently settles around an 'F' context. We can see that an F-minor scale is implied in spite of the absence of both the root and the dominant and with the move from C# in bar four to what would be the leading note of an F scale, E-natural, in bar five this suspicion seems to be cemented. However, no sooner have I begun to trust in this conclusion than a B-natural enters in bar six. I find it very difficult to tell whether, in the first instance, I hear this as an appoggiatura still in the key of F-minor moving down to the fourth of that scale, the B-flat, or whether I immediately switch to an E-major tonality since the bass line continues to state that note and the interval of the dominant is so seductive to our tonally conditioned ears? Perhaps there is a little of both, or perhaps either/or depending on each listening. Whichever is true it is not long before a distinctive brightening confirms which of these leads to follow. As the bass line presents a more solid statement of E in bar seven, the flute moves to the dominant of E-major (here an E flat) followed by the third (the A-flat) at the opening of bar eight.

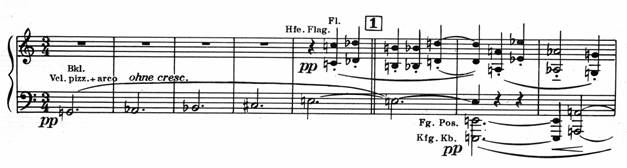

Example 2 © 1997 by Universal Edition (Vienna)

Over the next few bars tonal inferences become progressively more assured (Example 2). The double bass movement down a major third at the end of bar nine going into bar ten combined with the strong F in the clarinet and oboe form an unmistakably solid tonal centre (in this instance around B-flat major) so much so that by the time we reach figure two there is no longer a need to search for hints of major modality, on the contrary I have come to feel almost disappointed by their blatant representation.

As the song continues, even before the voice enters, Berg introduces a downward fall of a sixth from D to F#, the first instance of which is heard at the end of the oboe melody in bar twelve. Example 2 highlights the occurrences of this motif over the next few bars of music; the dense repetition of which places it firmly in the foreground of the tonal texture. This interval obviously brings with it a sense of D-major, and throughout this passage, despite the predominantly twelve-tone surrounding environment; Berg's constant insertion of this downward movement infers both a D-major chord and that of B-minor. As I listen the saturation of this familiar interval becomes overbearing and I find myself inadvertently occupied by the anticipation of its next appearance. This uncontrollable reaction forces me to confront a facet of my listening process that might be termed a "hierarchy of perception". My behaviour towards the repeated interval compels me to acknowledge the manner in which I have been conditioned to prioritise tonal references within a harmonic texture, no matter how unwelcome I find the resulting sonority.

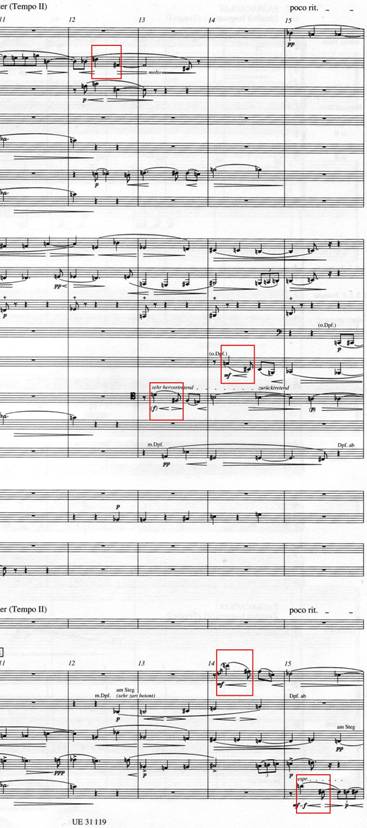

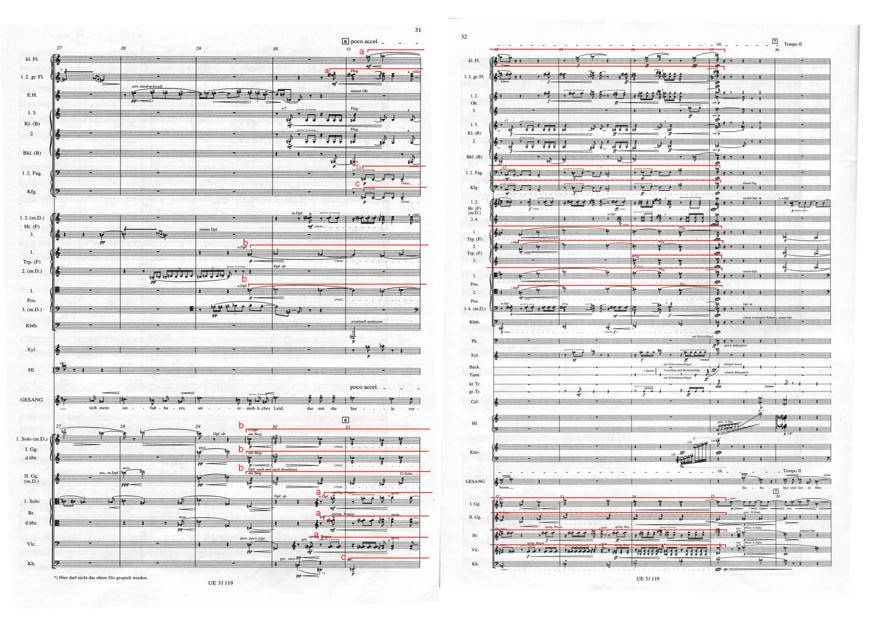

Example 3 © 1997 by Universal Edition (Vienna)

I am going to look at one more example from the song before I return to Kristeva's theory of abjection7. Towards the centre of the song the dramatic tension raises significantly as Berg increases the rhythmic pace, the thickness of the orchestration, and raises the dynamic to forte and ultimately fortissimo. All three of the principal themes are incorporated in this section (labelled a, b, and c in Example 3). The vertical weaving together of these chromatic lines heightens the level of dissonance so that by the trombone and bass fortissimo crotchet at bar thirty-four our tonal suspicions are seriously destabilised. However, the climactic culmination of these themes at bar thirty-five produces an unprecedented result of which Berg must have been fully aware. In what seems like a coincidence the combination of a, b, and c resolves to a flawless statement of the chord of A-major.

The powerful emotion of anticipation that has been built throughout the section by the choice of instrumentation, texture, and, most effectively through the dissonant colour, is immediately lost as I find myself in a tonal situation. The complete familiarity that I feel with the A-major chord, a combination of tones with which we are so accustomed, translates as sickly and unwelcome in this setting. As I listen, the insertion of this crude statement of traditional musical language at this precise moment forces me to recoil from that which I have been searching for all along. No comfort can be found in this familiarity; instead the chord forces me to recognise the want on which the twelve-tone language is founded.

I hope to have shown that, as listeners educated in our western tradition, we are programmed to try to locate a tonal centre as we listen to music. I hope to have also demonstrated that as we identify hints of such a centre, or more acutely, if we are actually faced with an unquestionable centre (as in Berg's climax), that desire becomes repulsive to us. Kristeva gives our loathing of a piece of food, or of the excremental as examples of abjection since we are fascinated by them and led towards them even though we know of their repugnance. She labels this the "shame of compromise", stemming from the knowledge that we are in the middle of treachery as we approach the abject food or filth. It is not the lack of cleanliness or health of these things that causes abjection; instead it is the way in which they disturb identity, system, and order through this compromise. The constant conscious threat of things that reside at our emotional borders simultaneously forms our subjective boundaries and beseeches our attempts at any kind subjective unification. What the abject reveals is, in Kristeva's words, the "inaugural loss" that laid the foundations of our beings.

When listening to this music, my search for tonality is both instinctive and seductive, and yet I am concurrently aware of the innate dangers of my modal prioritization. The shame that I feel as I helplessly compromise my objective listening in order to engage in a search for recognisable tonal points is not a criticism of tonality itself. On the contrary, this reaction is an essentially narcissistic one; it reveals nothing but the instability of my own ego. Abjection of a corpse for instance does not come about as a result of the absent soul of the cadaver itself. My repulsion is a subjective experience: face to face with death I am shown that which must constantly be thrust aside in order for me to live – I am at the border of my condition as a living being. This extreme illustration can serve as an analogy for our perception of tonality in a twelve-tone work. I am not proposing that tonality is repellent in essence; instead I wish to argue that our preoccupation with locating something of the tonal tradition when we listen, the way in which we are inescapably drawn to any tonal inference, highlights what is wanting in the twelve-tone language.

Perhaps a better analogy, though certainly a loaded one, is the example that Kristeva gives of abjection of the mother from whom we must liberate ourselves in order to become functioning human subjects. Our attempt to release this hold of maternity is a violent, clumsy breaking away that involves the constant risk of falling back under the sway of that power from which we have broken. This process can be compared to the attempted break from traditional tonality and free atonality that can be found at the centre of the twelve-tone movement. Like any attempt to break from one's ancestral heritage, the result is evolutionary and yet it will never manage a complete unfettering. I suggest that, like the denial of the maternal chora, a break from tonality is both necessary for the ongoing development of musical syntax but constantly carries with it, at the borders of its definition, that which it rejects.

As I listen to the Passacaglia of the Altenberglieder, Berg's blatant splitting of the tonal languages prevents me from choosing to listen to the song as completely atonal. The contrapuntal texture of a passacaglia necessarily highlights intervallic relationships and, as seen in the examples above, these are commonly and often explicitly tonal in orientation. As I listen to the 'new' musical language, any detection of traditional tonality disturbs its unity or self-sufficiency. Far from acting as a correlative, here tonality is present in opposition. Berg's setting draws the listener's attention to what is missing in twelve-tone music, emphasizing the powerful role of the absent. The repulsion that I experience originates in this disruption of my desired unity. The manner in which we have been so forcefully tonally conditioned results in our failure to completely renounce that founder language, instead it resides at the very edge of the twelve-tone topos and consequently any aural confrontation with it is threatening, disruptive and therefore repugnant.

I hope this discussion goes some way to illustrating my reasons for believing that, in twelve-tone music, tonality has not been abandoned – tonality has been abjected.

1 This paper was first presented at the RMA Research Students' Conference in Durham, 30 March–01 April 2006 Back

2 See for example, Revolution in Poetic Language, trans. Margaret Waller (New York: Columbia University Press, 1984); 'From One Identity to the Other', Desire in Language: a Semiotic Approach to Literature and Art (New York: Columbia University Press, 1980); and Powers of Horror: an Essay on Abjection, trans. Leon S. Roudiez (New York: Columbia University Press, 1982) Back

3 Tom Huhn, ed., The Cambridge Companion to Adorno, p.246 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004) Back

4 Leonard B. Meyer, Music, the Arts, and Ideas (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1967) Back

5 Claude Lévi-Strauss, The Raw and the Cooked (London: Pimlico, 1994) Back

6 Alban Berg, Fünf Orchester-Lieder (Vienna: Universal Edition), UE 31119 Back

7 Don Harris, ed., trans. Juliana Brand and Christopher Hailey, The Berg-Schoenberg correspondence (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1987) Back

8 Kristeva, Powers of Horror: an Essay on Abjection (New York: Columbia University Press, 1982) Back

© Carla Whalen, 2005