The courtly dame who features in the fin’ amours (so called ‘courtly love’) chansons of the trouvères was often elevated to the status of a religious icon, and was associated with the Virgin Mary in particular.1 Similarly to the Virgin, her attentions or embrace are described as a paradisical experience: she was attributed an almost divine power over the life, death, and well-being of the lover; she possesses superlative beauty; and is inspiring to the point of martyrdom. The lover adores and implores her, and claims that her love would improve his worth and save him from death by lovesickness. His adoration for this mortal dame seems almost blasphemous at times; one trouvère writes: ‘Je l’aour con mon sauvement /… car je n’ai autre saveour. / A lui aclin, a lui aour.’ (I worship her as my salvation /…for I have no other saviour. / I bow to her, I worship her.)2 Gillebert de Berneville’s J’ai souvent d’Amors chanté is particularly reminiscent of religious texts:

|

Le vous creant, Que la lune tost luisant Soleil en esté Passe de fine clarté; N’a son semblant Ne se prent, N’a la tres grande biauté Ne au doz ris De la bele Bietriz. Clers soleus sanz tenebror Enluminiz Passe toute autre luor. |

I assure you. That with its bright light The summer sun surpasses The most gleaming moon; Yet it does not compare To the appearance To the great beauty, To the sweet smile Of fair Beatritz. The bright sun, radiant, And untouched by darkness, Surpasses all other light.3 |

He was undoubtedly aware of the symbolism implied by describing his dame as more beautiful than creation, and by likening her to the sun. Her being ‘untouched by darkness’ implies her moral purity and intact virginity, and this is reminiscent of the Virgin Mary. His words were brought to mind upon reading an anonymous trouvère description of the Virgin: ‘…envers li sont li solauz et la bele tenebrous a vëoir’ (…beside her the sun and moon are dark to behold).4

The Holy Land crusades and the Albigensian crusades in Occitania helped to inspire a new religious enthusiasm, and the thirteenth century was an age of increasing piety. Christian doctrine was debated with a renewed vigour, by both laity and clergy, and there was a huge expansion of the Cult of the Virgin Mary. Some moralists began to object to secular lyrics and the woman-worship therein. During this time some trouvères began to make chansons pieuses (devotional songs) often in honour of the Virgin, many of which are contrafacta of chansons d’amour, and which share elements such as the melody, metrical structure, rhyme scheme and sounds, vocabulary and imagery of their secular models. As Bec notes, it is somewhat paradoxical that this phenomenon was simultaneously both a reaction against, and an imitation of, the secular lyric.5

Because chansons d’amour so often used religious language and symbolism to refer to the dame, many of them ‘… require[d] few changes to transform the grief, desire, or pleasure associated with worldly love into that occasioned by the contemplation of the Passion, the adoration of Christ or the Virgin, and the bliss of spiritual union with God.’6 The dame and the Virgin were both attributed with physical and moral perfection, and pleas to the courtly lady for her mercy easily became pleas to ‘Our Lady’ for her intercessions with God. Richard of Saint Lawrence in his De Laudibus of c1239–1245 wrote that just as the courtly lover must have ‘… loiauté, vaillance, souffrance, courtoisie, franchise, plaisance … the righteous ought to be jongleurs of Christ, Mary, and the saints: for the jongleurs of the court are wont to compose songs for… those from whom they have received or hope to receive great gifts.’7

There are, however, some significant differences in texts about the courtly lady and about the Virgin: whereas Mary’s motherhood is emphasised, this aspect of the dame is not mentioned. While the lover of the dame claims that he is a worthy but often unsuccessful suitor, those devoted to Mary confess their unworthiness, yet rejoice that their love is nonetheless bound to be reciprocated because divinity is ever-merciful. Some poets explicitly compare the two ladies in order to emphasise only their differences and the superiority of Mary over earthly women:

|

Bien sont cil fol et plain de vanité Qui font chançons ne d’Iseut ne d’Alaine Et sage sont tuit cil qui ont chanté De la Dame qui porta Dieu sanz paine … Avugles est, et s’abat de son tour Qui en biauté de cest siecle se fie. Regardés bien ces dames chascun jor: Beles sont hui, damain ne serront mie. S’un pou de mau les prent ainz le quart jor, Seront eles plus jaune que sofie. Bien les poöns conparer a la flor Qu’en queut matin, Au soir pert sa color. |

They are foolish and full of vanity, Those who make songs about Isolde or Helen, And they are wise who have sung about the lady Who bore God without pain. … He is blind and falls down from his tower Who takes pride in the beauty of this world. Take a good look at these ladies each day: Lovely today and not at all tomorrow. If a little quartan fever takes them, They turn more yellow than sulphur. We can well compare them to a flower Which one seeks in the morning, And by evening it fades.8 |

Similarly to the Marian contrafacta of chansons d’amour discussed above, pastourelles were also adjusted for religious purposes. The linguistic similarity between the names of the pastourelle heroine ‘Marion’ and the Virgin ‘Marie’ was easily exploited, as was the parallel between the earthly flowers associated with pretty maiden shepherdesses and the ‘fleur de paradis’ that is the Virgin Mary. Flowers (particularly the rose), having multiple related and interchangeable meanings, were especially useful symbols for the thirteenth-century artists who radically blurred the established boundaries of the sacred and profane. Sometimes there is a deliberately risqué – almost blasphemous – ambiguity in their work, and the desire expressed could be either spiritual, sexual, or both at once. Gautier de Coinci’s Marian work Les Miracles de Nostre Dame contains the following chanson pieuse, which is based on a pastourelle:

|

Hui matin a l’ajornee, Toute m’ambleure, Chevauchai par un pree Par bone aventure. Une florete ai trovee, Gente de faiture; En la flor, qui tant m’agree, Tournai lues ma cure. Adonc fis vers jusqu’a six De flor de paradis. Chascun lou qui l’aim et lout. O, o, o, o, o, n’i a tel dorenlot, Por tout a un mot. O, o, o, o, sache qui m’ot Mar vi, mar ot Qui let Marie por Marot |

This morning at day break, Going along, I was riding by a meadow By good fortune, I found a little flower, beautifully formed; To this flower, which was so pleasing to me, I turned my cares. And I made six verses On the flower of paradise. Everyone should love and praise her O, o, o, o, o, there is no ditty like this In a word O, o, o, o, let him who hears me know it is better to be blind or deaf than to be he who leaves Mary for Marot.9 |

The song retains many pastourelle characteristics, such as its opening lines, its bucolic setting and its nonsense syllables,10 and so the listener expects the poet to recount his seduction of the ‘florete’ of line 5. Line 11, however, reveals that this ‘florete’ is in fact the ‘flor de paradise’; the Virgin Mary. As Bec indicates, line 5 (‘une florete ai trovee’) was clearly inspired by the line ‘une pucelle ai trovee’ from the pastourelle version.11 The word ‘florete’ is equally appropriate as a reference to the flower-like beauty of the shepherdess or to Mary the ‘flower of heaven’, and this ambiguity is surely deliberate on the part of the poet.

However, whereas the courtly dame of the chansons d’amour already had a somewhat Marian, almost holy, untouchable air about her, the shepherdess was very much a physical, sexual being, and hence bears less of a resemblance to the Virgin. Some poets emphasized the differences rather than the similarities between the two women. Indeed the final lines of the above example compare the shepherdess directly and unfavourably with Mary, saying that it would be a foolish mistake to leave ‘Marie’ for ‘Marot’.

Secular female-voiced songs were also used to create religious works. The chanson de femme theme of a woman longing for her lover was used as a model for expressions of the soul’s longing for Christ. For example, Li amoureus m’ont doucement requinze is a woman’s lament for her lost beloved attributed to the Duchess of Lorraine, and was altered slightly to function as the soul’s lament for the crucified Christ. It is also used as an elaboration on Song of Songs 1:12 in Cantiques Salemon; an Old French version of Song of Songs Chapters I–III, which celebrates the mystical marriage of Christ to the human soul.12

The female-voiced lyric An paradis bel ami ai is only distinguishable as a chanson pieuse as opposed to a secular love song by its references to paradis and Diex in the refrains and in the penultimate line (line 23) of the last stanza:

Refrain 1

|

An paradis bel ami ai Tout deduisant en chanterai |

I have a handsome friend in heaven Merrily I will sing of him. |

Refrain 2

|

En paradis bel ami ai E! tres dous Diex, quant vous verrai? |

I have a handsome friend in heaven Oh! Dear sweet Lord, when will I see you? |

line 23

|

Ce est li rois de paradis |

It is the king of heaven13 |

The remainder of the song sits comfortably in either a secular or sacred register, and could quite conceivably be a contrafactum of a lost secular chanson. To illustrate this point, Bec has produced a secular version of the song by altering only the refrain and lines 11 and 23.

Women are frequently the lyric ‘je’ voice as well as the subject matter of lower-style songs that were apparently sung in caroles (outdoor public dances), and which have been preserved through quotations in chansons, motets, romances, sermons, and other works. Following a brief survey of Tischler’s collection,14 it seems that there are three basic types of female-voiced dance lyric (although most songs combine, vary and derive from these elements): C’est la gieuse, Bele Aeliz, and malmarieé. In the C’est la gieuse type women encourage one another to go to the meadows/woods/olive tree/fountain/seashore, to dance and meet lovers. The character of Bele Aeliz is ‘… beautiful, amorous, and inclined to song,… her behaviour generally involves rising early, getting dressed up in her finery, and going outside to gather flowers or meet her lover.’15 Chansons de malmarieé give voice to unhappily married women defying spies, gossips, and their jealous husbands by meeting their lovers. The following carole song combines elements from all three themes:

|

Main se leva bele Aeliz. Dormez, jalous, ge vos en pri! Biau se para, miex se vesti Desoz le raim. Mignotement la voi venir Cele que j’aim. |

Bele Aeliz rises early. Sleep, jealous one, I’m going to the meadow! She prepared herself and dressed beautifully Beneath the leaves. Sweetly I will go To the one I love.16 |

The dramatic expansion of cities that took place from 1150–1300 resulted in the various elements of society mixing more than they previously had. Hence preachers witnessed the caroles danced through the streets and on the rural land that was now incorporated within the new town walls. Many of them became concerned that these dance songs encouraged women in vanity and adultery, and discourage chastity and marriage. Some spoke out against this directly: Dominican Jaques de Vitry uses the figure of Bele Aeliz in a cautionary tale for the consequences of immoral behaviour: ‘And in this way women, when they have to go out in public or elsewhere, spend a great part of the day preening themselves. When Aeliz had gotten up and when she had washed, and the mass had been sung, devils carried her away.’17 Friar Guillaume Peyraut was particularly vehement in his dislike of carolling women. His Summa de Vitiis et de Virtutibus of c1249 rails against dancers performing on sacred cemetery ground, which had now been incorporated into the new town walls. He condemns carollers for holding hands and clapping and stamping, and he found it particularly shocking that the women would dress up on church feast days, wearing garlands, make-up, and wigs made from the hair of the dead. He even likened carolling women to apocalyptic monsters in the book of Revelation.18 Others took the very elements of secular song that concerned them, such as the sexualized female characters and the anti-marriage attitudes, and reinterpreted them to serve a pious function. Archbishop of Canterbury Steven Langton, for example, used the figure of Bele Aeliz as a representation of ‘the mother of mercy and the queen of justice who bore the king and Lord of the heavens.’19

In an article published in 1920, C. B.Lewis made the fascinating proposal that the Bele Aeliz theme has its origins in the Apocryphal Gospel story of Saint Anna, the mother of the Virgin Mary.20 The scripture says that Anna ‘washed her head, put on her bridal garments, and … went into her garden to walk there. And she saw a laurel tree and sat down beneath it’.21 The resemblance between Anna’s actions and Bele Aeliz’s preparing herself and dressing beneath the leaves, and going to a meadow is indeed intriguing. If Lewis is correct, then it is remarkable – and fitting – that churchmen, working against the immorality of Bele Aeliz, but apparently unaware of her scriptural roots, should have turned her into a sacred figure once more, by transforming her into Saint Anna’s daughter the Virgin Mary.

Chansons de malmarieé were recontextualized so that their denouncement of marriage was interpreted as being for the sake of holy celibacy rather than for lovers and adultery. In the prologue to Les miracles de Nostre Dame, Gautier de Coinci refutes caroles as ‘… gabois et legeries… chans de lecheries…’ (… mockery and trivialities… songs of lechery…),22 but then proceeds to lace his work with pious songs modelled on secular ones. Les miracles includes a sermon entitled ‘De la chastée as nonains’, which he precedes with a citation of a popular malmariée refrain, using it to encourage nuns to ‘prize chastity and to welcome the chance to forgo… earthly marriage in favour of a heavenly marriage with Christ’23:

|

Mal ait cil qui me marai! Ce dïent en lor chançonnetes |

Curses to him who married me! So they say in their songs. |

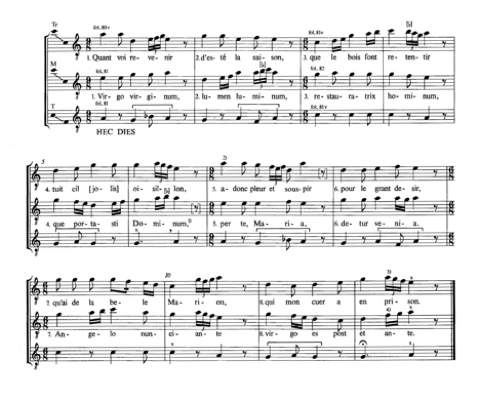

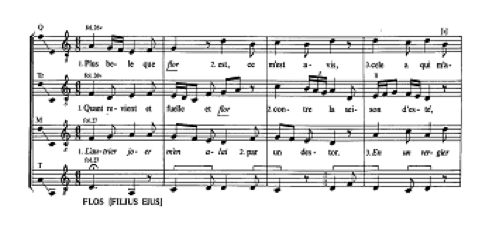

Secular lyrics were also given a new sacred context by their juxtaposition with French or Latin religious texts in motets. The motet Quant voi revenir/Virgo virginum/HEC DIES of the Montpellier Codex (example 1), for example, combines an Old French secular love song for a certain ‘bele Marion’ with a Latin piece for the Virgin.24In the last line the triplum sings: ‘ … le grant desire / qu’ai de la bele Marion, / qui mon cuer a en prison’, (… the great desire / I bear for the fair Marion, / who keeps my heart in prison), while the motetus declares: ‘Angelo nunciante / virgo es post et ante.’ (At the angel’s heralding / you are a virgin before and after.) The words ‘bele Marion’ in the triplum part are immediately followed by ‘virgo es post et ante’ in the motetus, and the melodic lines of these two voices overlap at this point – the triplum falling from ‘a’ to ‘d’, now singing beneath the motetus which has risen from ‘e’ to ‘g’. Depending on factors such as the timbre and blend of the performers’ voices, the highest-pitched notes may be the most prominent, and hence the listener’s attention may be focussed on the words ‘bele Marion’… followed by ‘virgo es post et ante’. This could refer to either – or both – the virginity of Mary or the continuing virginity – despite the desires of the triplum singer – of ‘bele Marion’. As Stakel comments, ‘the angel’s message seems to bear ironically on the French lover’s distress.’25 The tenor line is drawn from the Easter Sunday gradual ‘Hec dies, quam fecit Dominus: exultemus et laetemur in ea. V: Confitemini domino quoniam bonus: quoniam in saeculum misericordia ejus.’ (This is the day that the Lord has made: let us rejoice and be glad in it. Give praise unto the Lord for He is good: for His mercy endureth forever), taken from Psalm 117: 24 and 29. This choice of text seems to remark ironically upon the fruitlessness of the triplum’s unrequited love for a merciless mortal woman, by comparing it to the unfailing nature of divine mercy. Its celebration of forgiveness re-enforces the motetus’ prayer to the Virgin – the ‘restorer of mankind’ – for pardon. Its Easter-time rejoicing also resonates with the triplum’s springtime motif, and the Paschal theme of new beginnings after repentance is appropriate for the motet’s implication that true fulfilment in love is only possible if one turns from loving earthly ladies for the sake of Our Lady.

Example 1: Anon., Quant voi revenir/virgo virginum/HEC DIES, in Tischler and Stakel, The Montpellier Codex, IV, p.25

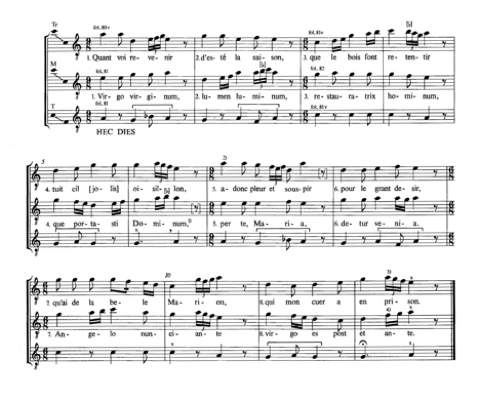

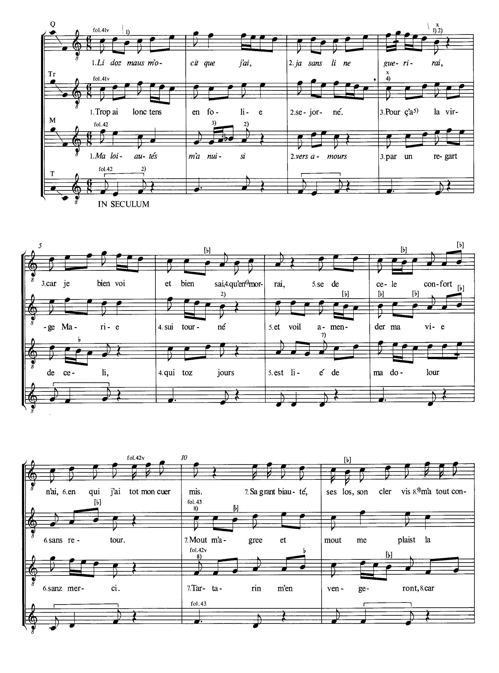

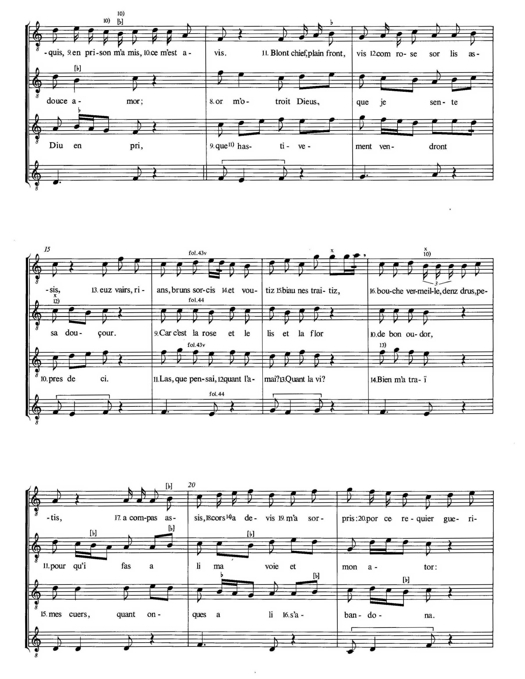

The tenor line IN SECULUM, also from the Easter Sunday gradual HEC DIES, is used with the same significance another Montpellier Codex motet (example 2). The quadruplum is a typical trouvère love lyric: the singer claims that he is imprisoned by, and dying of love, and that only his lady can save him. Making use of the flower motifs discussed above, he describes her as having a complexion ‘com rose sor lis asis’ (like rose set against lily white). Conversely, the triplum insists on the folly of worldly love, declaring: ‘Trop ai lonc tens en folie sejorné’ (I have lived foolishly for quite a long time), and that he is now devoted to the Virgin Mary instead. Echoing the quadruplum’s description of his earthly lady, he sings of his heavenly beloved: ‘c’est la rose et le lis et la flor / de bon oudor’ (she is the rose and the lily and the sweet-scented blossom). The melody of this phrase runs in parallel fifths with the tenor. Hence the combination of these two voices emphasises the triplum’s rejoicing in unfailing divine mercy that the tenor’s IN SECULUM text celebrates (see example 2, bars 16–18). The motetus repents of an earthly love that has caused him pain, and these sentiments could easily be used in support of the Marian devotion found in the triplum.

Example 2: Anon., Li doz maus/Trop ai lonctens/ma loiautés/IN SECULUM, in Tischler and Stakel, The Montpellier Codex, pp.53–5

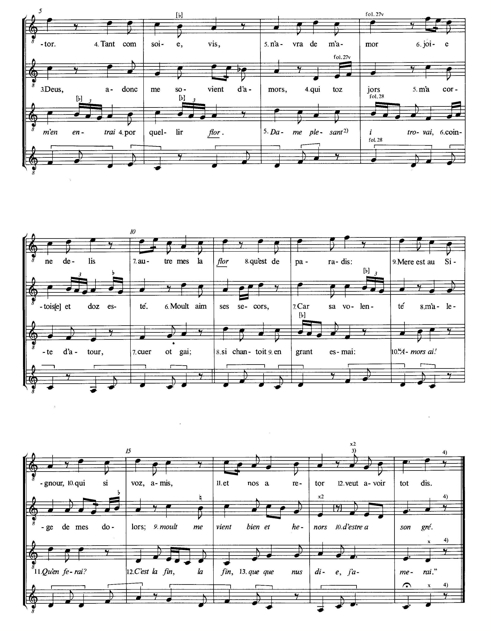

The motet Plus bele que flor/Quant revient et fuelle et flor/L’autrier joer m’en aller/FLOS (example 3) also has a prominent floral theme, which is used to interweave references to courtly, pastoral and Marian experiences of love. The word ‘flor’ is sung twice by the quadruplum, and once each by the triplum and motetus: the quadruplum sings of the Virgin Mary, who is ‘Plus bele que flor’ (more beautiful than a flower), and who is ‘la flor / qu’est de paradis’ (the flower that grows in paradise). The triplum begins with an opening statement typical of trouvère chansons d’amour: ‘Quant revient et fuelle et flor/ contre la seison d’esté…’ (When the return of leaf and flower/ signal the arrival of the summer season…), and the love song that follows would be equally appropriate for either a heavenly or an earthly lady. The motetus recounts that he entered an orchard to pick some flowers and met a maiden there. (The maiden and her virginity are, of course, the metaphorical ‘flowers’ that he desired.) The tenor line FLOS is taken from the Messianic prophecy of Isaiah 11: 1–2: ‘Stirps Jesse produxit virgam: virgaque florem. Et super hunc florem requiescit spiritus almus. V: Virgo dei genetrix virga est, flos filius ejus.’ (The stalk of Jesse produced a branch: and the branch a flower. And upon this flower the bountiful spirit came to rest. The Virgin mother of God is the branch, the flower is her son.’) This is used as a responsorial for the feasts of the Assumption and of the Nativity of the Virgin. The liturgies of these feasts also incorporate readings from Song of Songs, which have strong resonance with our motet through their references to gathering flowers in a garden, and through the allegorical Marian interpretations that were so often imposed onto the book’s erotic content.26

Example 3: Anon., Plus bele que flor/Quant revient et fuelle et flor/L’autrier joer m’en aller/FLOS, in Tischler and Stakel, The Montpellier Codex, pp.39–40

Female-voiced songs were likewise given a religious perspective by their incorporation in motets. The motetus part of Je ne mi marierai/AMORIS is built from two female-voiced refrains that present a young girl determined to avoid marriage, for the sake of the freedom and excitement of seeing boyfriends:

|

Ja ne mi marierai, Mais par amors amerai. Ne vous mariez mie, Tenez vous ainsi. |

Never will I marry Rather will I love. Do not marry Keep yourself this way.27 |

The first refrain (lines 1–2) also appears in the song Chançon vueill faire de moi, in which a girl celebrates her lies to her lover and vows not to marry anyone who will not allow her to continue in her playful lifestyle. However, the motet juxtaposes the refrains with a tenor line AMORIS, taken from an Alleluia from the liturgy of Pentecost week, which reads: ‘Alleluia. Veni sancte spiritus, reple tuorum corda fidelium, et tui amoris in eis ignem accende.’ (Alleluia come holy spirit fill the hearts of your faithful ones and kindle the fire of your love in them.) This puts the Ja ne mi marierai text in a new light, now implying the rejection of earthly marriage for the sake of a spiritual marriage with Christ, and for keeping a vow of celibacy as advocated by St Paul in his First Letter to the Corinthians:

Now to the unmarried and the widows I say: it is good for them to remain … An unmarried woman is concerned about the Lord and is to be devoted to the Lord in both body and spirit. But a married woman is concerned about the affairs of this world – how she can please her husband.28

As Huot explains, ‘although from one perspective the virgin and the adulteress are an absolute contrast, from another perspective, they both exist outside normal marital bonds… [they share] a common valorization of private passion: a love more noble, or at least more pleasurable, than that in institutionalized marriage.’29 Hence, the morally problematic character of the adulteress is transformed into an advocate of Christian chastity.

The upper part of the motet Renvoisiement/HODIE is built from two female-voiced refrains that are immediately identifiable with the secular songs and dances of amorous girls and their lovers:

|

Renvoisiement i vois a mon ami; Ainsi doit on aler a son ami. |

Joyfully there I go to my beloved; So one should go to her beloved.30 |

The latter of these two is also found in the following rondeau:

|

Ainsi doit on aler A son ami. Bon fait deporter, Ainsi doit on aler Baiser et acoler, Pour voir le di. Ainsi doit on aler A son ami. |

So one should go To her beloved It is good to play So one should go To kiss and embrace Truly I say so. So one should go To her beloved.31 |

The tenor part of the motet is taken from an Alleluia for the Assumption of the Virgin Mary, provides a less obvious, but equally plausible religious interpretation of the motetus text, wherein we see Our Lady joyfully going to her beloved Christ: ‘Alleluia. Hodie Maria virgo caelos ascendit. Gaudete quia cum Christo regnat in eternum.’ (Alleluia. Today the Virgin Mary ascends to heaven. Rejoice, for Christ reigns eternally.) The two refrains of the motetus text are again put into a sacred context by their inclusion in Gautier de Coinci’s thirteenth-century poem Court de Paradis, which describes a heavenly carole of saved souls led by Jesus, the Virgin Mary and Mary Magdalene. Renvoisiement i vois a mon ami is assigned to a group of virgins, and Ainsi doit on aler a son ami to married women, and they sing their respective refrains as they move towards Christ.32

The two texts of the following example refer to female dance leaders who encourage other women to keep their lovers and cuckold their husbands:

Triplum

|

Li jalous par tout sunt fustat En portant corne en mi le front; Par tout doivent estre haut. Le regine le commendat, Que d’un baston soient frapat Et chacié hors comme larron. S’en dançade veillent entrar, Fier les di pie comme garçon. |

Everywhere the jealous are thrashed And wear a horn in the middle of their foreheads They should be jeered by everyone. The queen commands That they be beaten with a stick And driven away like thieves. If they want to take part in the dance, Kick them with your foot, as you would a boy. |

Motetus

|

Tuit cil qui sunt enamourat Viegnant dançar, li autre non. La reigne commendat (Tuit cil qui sunt enamourat), Qui li jalous soient fustat Fors le dance d’un baston. Tuit cil qui sunt enamourat Viegnent avant, li autre non. |

All those who are in love May come and dance; the others, no. The queen commands (All those who are in love) That the jealous be Driven away from the dance with a stick. All those who are in love May come forward; the others, no. |

Tuit cil qui sunt enamourat is extant in rondeau form,33 and its refrain lines: ‘Tuit cil qui sunt enamourat, viegnent avant, li autre non’ also appear as sung by the Virgin Mary in Court de Paradis, as she invites all Christ-loving souls to join the heavenly carole, while rejecting the unfaithful and unworthy. Thus, the queen of the dance is easily transformed into the Queen of heaven, and ‘the separation of lovers from nonlovers, a frequent motif in the refrain repertoire, is easily applied to the distinction of the saved and the damned.’34 When they appear in motet form,35 the two texts are set against the tenor VERITATEM, which is taken from a gradual for the Assumption of the Virgin Mary: ‘Propter veritatem et mansuetudinem, et justiutiam: et deducet te mirabiliter dextera tua. Audi filia, et vide, et inclina aurem tuam: quam concupivit rex speciam tuam.’ (For truth and mercy and justice and your right hand will lead you marvellously. Listen daughter and behold, and incline your ear, for the king has desired your beauty.) Hence the vernacular texts are again coloured with religious meaning: the saved souls (those who love Christ) are invited into heaven, the unworthy are rejected and sent away by the Queen of paradise, and the source of the tenor (‘the king has desired your beauty’) now suggests Christ’s desire for the love of mankind.

Some motets satirize the sexualized female characters of secular love songs by contrasting them with images of chaste Christian women. For example, the female voices heard in the upper parts of the motet Si com aloie jouer/Deduisant/PORTARE are markedly determined to take lovers and cuckold their husbands.36 They even ask: ‘Pleüst a Diu, que chascune de nous / tenist la piau de son mari jalouz!’ (May it please God that each of us / have the skin of her jealous husband!) The tenor is taken from an Alleluia for the Assumption of the Virgin Mary, and alludes to an image of womanhood starkly different to that of the adulteresses presented in the vernacular texts: ‘Alleluia dulcis virgo, dulcis mater, dulcia ferens pondera, quae sola fuisti digna portare regen caelorum et dominum.’ (Alleluia, sweet Virgin, sweet mother, bearing the sweet weight, you alone were worthy of carrying the Lord, King of Heaven.)37 In another instance, the same tenor is paired with the voice of a woman whose love Robin has bought with material gifts, and this invites the comparison of two opposite female personae: prostitute and Virgin:

|

Robin m’aime, robin m’a, Robin m’a demandee, Si m’avra. Robin m’acheta corroie Et aumonniere de soie; Pour quoi donc ne l’ameroie? Aleuriva! Robin m’aime, robin m’a, Robin m’a demandee, Si m’avra. PORTARE38 |

Robin loves me, Robin has me, Robin asked for me, So he will have me. Robin bought me a belt And a silk purse Why then would I not love him? Aleuriva! Robin loves me, Robin has me, Robin asked for me, So he will have me! |

And so the religious enthusiasm of thirteenth-century France, its complex attitudes to women, and the flowering of the Cult of the Virgin Mary were manifested in Old French song in a number of interesting – and sometimes surprising – ways. Composers exploited the structural and technical elements as well the vocabulary and imagery of secular song forms in order to create sacred works. The courtly dame, the shepherdess, the innocent maiden and the adulteress were compared, contrasted, even interchanged, with the Virgin Mary. The phenomenon was taken to more complex levels in motets, wherein various song types were juxtaposed so that they could comment upon one another and colour one another’s meaning through the interweaving of musical and textual lines. This interplay of the sacred and secular in song seems to have had two main purposes: firstly, it was intended to increase the popular appeal of Christianity, and secondly, these works were an exciting and experimental new art form; many-layered musical and literary games, which can be just as engaging and startling today as they would have been at the time of their creation.

1 ‘Courtly love’ lyrics are most often associated with the troubadours, who worked in Occitania mainly during the twelfth century. However, this article is concerned with the slightly later and much larger extant repertoire of the trouvères, who worked in northern France. Although there are some instances of Marian lyrics in extant troubadour song, the cult of the Virgin Mary became increasingly popular in thirteenth-century northern France and evidence from extant trouvère manuscripts suggests that the creation of pious contrafacta of secular song grew during this time. This could have been related to the increasing circulation of songs in written form. See M. O’Neill, Courtly Love Songs of Medieval France: Transmission and Style in Trouvère Repertoire (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006), pp.13–52. Also see this chapter for discussion of what is known about the gap between the composition of the songs and the compilation of the chansonniers and ch.3, pp.53–92, for information about the extant melodies. Back

2 Anon., D’amours vient mon chant et mon plour, in S.Rosenberg, M.Switten and G.Le Vot, ed. and trans., Songs of the Troubadours and Trouvères: An Anthology of Poems and Melodies (New York: Garland, 1998), p.233. Back

3 Gillebert de Berneville, J’ai souvent d’Amors chanté, lines 27–38, in Rosenberg, Switten and Le vot, Songs of the Troubadours and Trouvères, pp.338–9. Back

4 Anon., Chanter m’estuet de la sainte pucelle, in M. J. Epstein, ed and trans., Prions en Chantant: Devotional Songs of the Trouvères, Toronto Medieval Texts and Translations, 11 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1997), pp.230–31.Back

5 P.Bec, La lyrique français au moyen âge (XIIe–XIIIe siècles): Contribution à une typologie des genres poétiques médiévaux, Publications du Centre d’études Supérieures de Civilisation Médiévale de l’Université de Poitiers, 6–7, 2 vols (Paris: Picard, 1978), II, p.142 Back

6 S. Huot, Allegorical Play in the Old French Motet: The Sacred and Profane in Thirteenth-Century Polyphony (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1997), p.62 Back

7 Epstein, Prions en Chantant, pp.28–9 Back

8 Anon., Chançon ferai, puis que Dieux m’a doné, in Epstein, Prions en Chantant, pp.198–9. ‘Quartan fever’ is an archaic medical term for a malarial illness that recurrs every fourth day.

Back

9 Gautier de Coinci, Hui matin a l’ajornee, in M. Everist, French Motets in the Thirteenth-Century: Music, Poetry and Genre (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), pp.141–2. Everist cites a secular pastourelle version of this song extant as the motetus part of the motet Hyer matin a l’enjournee/BENEDICAMUS DOMINO.

Back

10 Pastourelles are typically past-tense narratives that tell of a knight who rides out and encounters a shepherdess (often named Marion) or observes a shepherdess with her lover (Robin). They have a more earthy tone than chansons d’amour. The most extensive study of this genre is that of W. D. Paden., ed. and trans., The Medieval Pastourelle, Garland Library of Medieval Literature, 34–5, 2 vols (New York: Garland, 1987). Back

11 Bec, La lyrique français, I, p.76 Back

12 Huot, Allegorical Play in the Old French Motet, p.75 Back

13 Anon., An paradis bele ami ai, in Bec, La lyrique français, II, p.67 Back

14 Anon., Main se leva bele Aeliz, in H. Tischler, ed, Trouvère Lyrics with Melodies: Complete Comparative Edition, Corpus Mensurabilis Musicae, 107, 15 vols (Neuhausen: American Institute of Musicology and Hänssler-Verlag, 1997), XIV, rondeau no.27 Back

15 Huot, Allegorical Play in the Old French Motet, p.57 Back

16 Anon., Main se leva bele Aeliz, in Bec, La lyrique français, II, p.150 Back

17 ‘Hujiusmodi autem mulieres quando ad publicam exire vel etiam ire debent, magnum diei partem in apparatu suo consummunt. Quant Aeliz fu levee, et quant ele fu lavee, et la messe fu chantee, e t deable l’en ont emportee’, in T.Hunt, ‘De la chanson au sermon: Bele Aalis et Sur la rive de la mer’, Romania, no.104 (1983), 433–45, trans. in Huot, Allegorical Play in the Old French Motet, p.60 Back

18 G. Peyraut, Summa de Virtiis et Virtutibus, trans. in C.Page, The Owl and the Nightingale: Musical Life and Ideas in France, 1100–1300, (London: Dent and Sons, 1989), pp.115, 196–8 Back

19 J. E.Stevens, Words and Music in the Middle Ages: Song, Narrative, Dance and Drama, 1050–1350 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986), p.177 Back

20 C. B. Lewis, ‘The Origin of the Aalis Songs’, Neophilologus, v, (1920), 289–97. As far as I am aware, this fascinating possibility has unfortunately not been explored any further since the 1920s.

Back

21 ‘The Protevangelum of James’ 2:5, in J. K. Elliot, ed. and trans. by M. R. James, The Apocryphal New Testament: A Collection of Apocryphal Christian Literature in an English Translation, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993), pp.57–8 Back

22 A. Butterfield, Poetry and Music in Medieval France: From Jean Renart to Guillaume de Machaut (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), p.105 Back

23 Ibid., p.113 Back

24 Anon., Quant voi revenir/Virgo virginum/HEC DIES, in H. Tischler, ed. and S. Stakel, trans., The Montpellier Codex, 4 vols, vol. 4 ed. and trans. by S. Stakel and J.C. Relihan, Recent Researches in the Music of the Middle Ages and Early Renaissance 2–8 (Madison, Wisconsin: A.R.Editions, 1978–85), IV, p.25 Back

25 Tischler, The Montpellier Codex, IV, p.xxi Back

26 Huot, Allegorical Play in the Old French Motet, p.91 Back

27 Ibid., p.107 Back

28 I Corinthians 7:8, 34, NIV Back

29 Huot, Allegorical Play in the Old French Motet, pp.112 and 115 Back

30 Ibid., p.83 Back

31 Anon., Ainsi doit on aler, in Tischler, Trouvère Lyrics with Melodies, XIV, rondeau no.2 Back

32 Huot, Allegorical Play in the Old French Motet, p.82 Back

33 Anon., Tuit cil qui sunt enamourat, in Tischler, Trouvère Lyrics with Melodies, XIV, rondeau no. 41 Back

34 Huot, Allegorical Play in the Old French Motet, p.104 Back

35 Anon., Tuit cil qui sunt enamourat/Li jalous par tout sunt fustat/VERITATEM, in Tischler and Stakel, The Montpellier Codex, IV pp.62–3 Back

36 Anon., Si com aloie jouer/Deduisant/PORTARE, in Tischler and Stakel, The Montpellier Codex, IV, pp.56–7 Back

37 Huot, Allegorical Play in the Old French Motet, p.111–12 Back

38 Anon., Robin m’aime/PORTARE, in Tischler and Stakel, The Montpellier Codex, IV, p.87 Back

© Rachel Brawn, 2008